The Four Kinetons/Kingtons of the Ardens: Vicecomital Nobility and Templar Co-Administration in Warwickshire

By Dr Stephen M. K. Brunswick, Ph.D., Th.D.

(Priory of Salem – St Andrew’s OCC Educational Series / Watchman News Historical Division)

Prefatory Note on Authority and Sources

This study follows the method of recognized genealogical authorities such as Evelyn Philip Shirley, Esq. M.A., F.S.A., former Knight of the Shire for Warwick, whose classic work The Noble and Gentle Men of England (London, 1859) remains a standard of reference in the peerage and county histories of England. See Appendix A for his concise summary on the noble origin of the Ardens of Longcroft, descended in the male line from the Saxon Earls of Warwick.

I. Introduction — A Forgotten Earldom in the Heart of England

Among the lost constructs of early English nobility stands the Earldom of Kineton, an estate of such breadth that Sir William Dugdale, in The Antiquities of Warwickshire Illustrated, called it “a dignity of earldom dimensions.” Its origins reach to the royal charter of King Edgar to Ælfwold (969 AD) — a ten-hide estate granted as “an everlasting inheritance” (eternal hereditas) at Cyngtune meaning King’s estate (latest transcription of such lands were written as Kineton and Kingston). This Saxon bequest became a cornerstone of the ancient Arden family, that remnant of Anglo-Saxon high nobility which alone survived the Norman conquest with baronial holdings intact.

Within this broad territory emerged four distinct but inter-related Kinetons (Kingtons) — localized seats that persisted through the Norman, Angevin, and Plantagenet ages as administrative anchors of Arden land:

-

Kineton in Claverdon Hundred, later associated with the Knights Templar of Temple Balsall;

-

Kington in Solihull (Bickenhill), forming the ecclesiastical link with the priory of Markyate;

-

Packington (Pa-Cyngtun), the western extension of the royal estate;

-

Preston Bagot (Kington adjacent), held conjointly by the le Notte and Bagot families.

Together they constituted what contemporaries called the “Four Kinetons of the Ardens.” Each bore the memory of the ancient cyng-tūn — the King’s enclosure — and each stood within the same cultural geography bounded by the Forest of Arden, Oxfordshire, and the marches of Worcestershire.

II. The Vicecomital Heritage of the le Notte Family

The le Notte (Nott) lineage arose from the vicecomital — that is, sheriff-earl — house of William of Oxford (d’Oilly) and his sons. In feudal terminology comes denoted an Earl; vicecomes, his deputy or hereditary sheriff. By the reign of Henry I, William’s heirs had received from the Crown the lands of Kineton, Warwick, and Worcester; one son, Milo de Kineton, is styled Vicecomes Oxoniæ in Dugdale’s transcripts of royal charters.

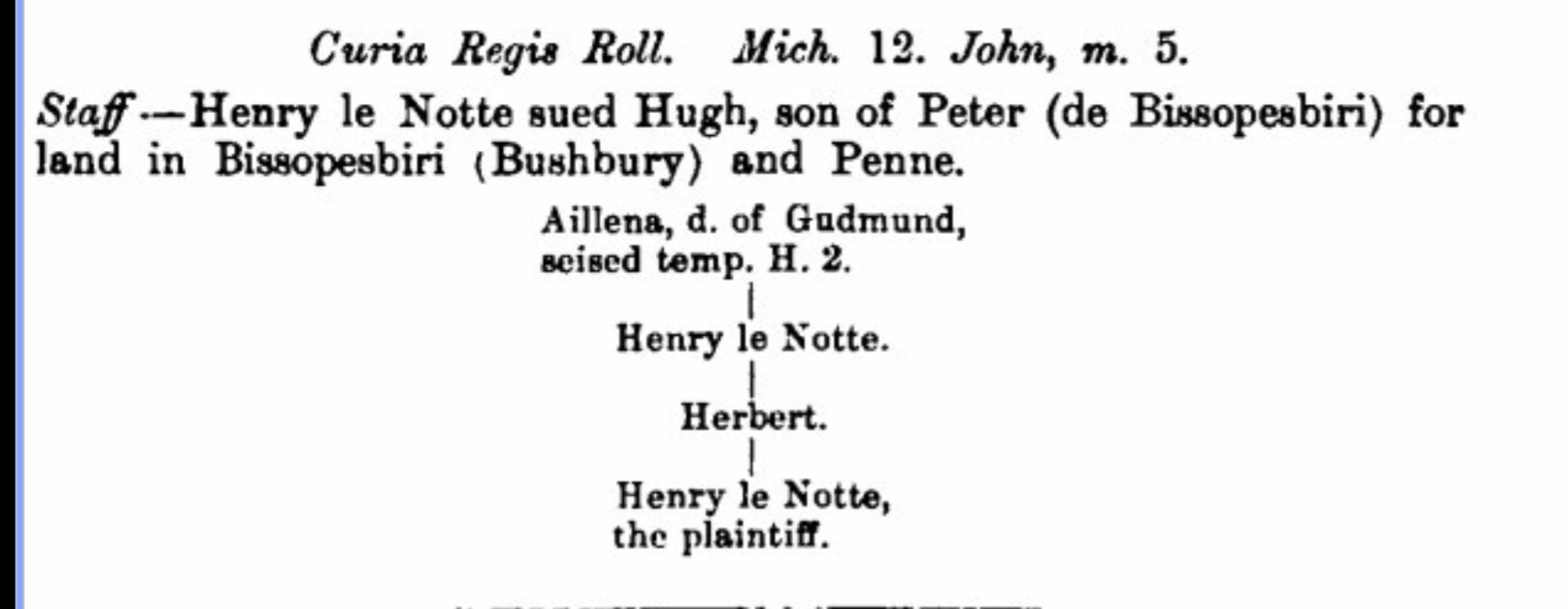

Keats-Rohan’s Domesday Descendants (pp. 288–308) confirms this sequence:

Godwin Reeve of Oxford → Eilwi → Henry of Oxford (d’Oilly) → Richard of Oxford, who married Æthelgifu (Aillena), daughter of Guthmund of Packington. From that union issued the feudal line of Milo de Kineton and ultimately John le Notte de Arden (1140–1190), whose descendants held the Four Kinetons of the Ardens in hereditary succession.

By the thirteenth century these vicecomital descendants functioned not as mere local gentry but as noble lords of knight’s-fee rank — that is, tenants-in-chief or sub-in-chief required to maintain a fully armed knight for royal service and thus counted among the formal nobility of England.

Yet the family’s vicecomital character did not end with feudal tenure. For centuries the le Nottes served as Sheriffs, Mayors, and Civic Magistrates of the realm. In Solihull and Warwickshire they were styled Sheriffs et Mayors of Solihull, while in London they rose to the office of Lord Mayor. The most famous, John Nott de Arden, as Sheriff and later Lord Mayor of London, enacted the historic Bye-Law against Usury — one of the earliest municipal bans on interest-taking in English history (Watchman News, 2023). He was a close neighbor and peer to the hereditary Sheriffs of Worcester, serving in concert with that office as a guardian of mercantile justice and public morality.

This vicecomital spirit continued for generations. Even in the late Tudor and early Stuart eras the family intermarried with other dynasties of equal rank and office. One example is John Nott VI of Thornbury-Kington (b. 1585, Bristol), Lord of Shelsley Beauchamp / Great Sheldesly, who married Ann Jeffrey, daughter of Lord William Jeffreys of Hom Castle, High Sheriff of Worcestershire for four generations and Lord of Clifton-upon-Teme. Their arms — Nott impaling Jeffreys — were quartered in the College of Arms as those of a vicecomital house, identical to the heraldry attributed to the Lord Mayor John Nott of London. Thus, from the Norman era to the seventeenth century, the le Nottes remained faithful to their ancestral identity as the Vicecomital House of Kineton — hereditary guardians of law, commerce, and the moral economy of England.

III. The Earldom Charter and the Eternal Inheritance

King Edgar’s 969 charter (S 773 — Sawyer Archive, Cambridge) granted Ælfwold ten hides “in Cyngtune” as an everlasting inheritance (in æce eardunga æhta). Witnessed by Archbishops Dunstan and Oscytel, it delineated borders consistent with the later Kineton Hundred. This is the earliest attested legal expression of an “eternal inheritance” in English land law — a clause echoed centuries later when the le Notte descendants reappear as holders of hereditary knight’s fees (feoda militum) in the same district.

Dugdale saw this continuity and deemed the district a “species of earldom.” Keats-Rohan refined that understanding by tracing the vicecomital descent from Godwin Reeve of Oxford to Milo de Kineton, showing uninterrupted noble service from the tenth to the thirteenth century.

IV. The Four Kinetons/Kingtons of the Ardens

1. Kineton (Claverdon Hundred)

le Domesday Book (1086) lists 1½ hides in Kington held of the Earl of Warwick, once the property of Britmod. By 1235 this estate was held by Henry le Notte de Kineton in conjunction with Preston Bagot — “forming with Preston Bagot one knight’s fee.” (Bk. of Fees I 508).

By 1316 the fee appears “in the hands of the Master of Grafton,” representing the Knights Hospitaller, (Rot. Hund. II 226), but the record of 1235–42 shows it was still the le Notte family’s Templar-aligned half-fee before that transference. Henry le Notte’s grant of lands “from the stream which comes from Preston by the brook of Chelewellesiche” to Bordesley Abbey (1275 entry) demonstrates an independent lordship co-operating with monastic orders.

2. Kington (Solihull / Bickenhill)

In 1199 Henry le Notte acquired a virgate in Kington from Richard son of Richard; his grandson Henry gave the advowson of Kington church to the Prioress of Markyate in 1221 and was still transacting land in 1235. Later generations — Thomas le Notte (1305–1314) and Henry his son (1332) — executed settlements “in Kington and Lyndon” with remainders to John and Prudence le Notte, confirming continuous hereditary tenure for two centuries.

This Kington was the spiritual seat of the family, lying within the Solihull parish where the Templar influence from Balsall was strongest.

The le Notte family for centuries were styled as Sheriffs as Mayors of Solihull, just as they were also Lord Mayors of London. To this day, the name sticks as the Mayor who banned usury at London (John Nott de Arden’s Bye-law against usury, as Sheriff and Mayor of London).

3. Packington (Pa-Cyntun / Pakington)

Linguistically, Pa-Cyntun signifies the enclosure at the hill of the King. The prefix Pa- (Old English pæc / paec, “hill or ridge”) combined with cyngtūn (king’s estate) yields “King’s ridge town.” This matches its landscape atop the Arden upland.

Guthmund of Packington, whose daughter Ailena married Richard of Oxford (grandson of Godwin Reeve of Oxford), united the Mercian and Arden lines — forming the genealogical hinge between the Arden earldom and the le Notte vicecomital descent.

The Nott family won several court cases as heirs of Knights fees, with this genealogy (to their ancestress Aillena) as the basis. Eg. Curia Regis Roll:

4. Preston Bagot (Kington adjacent)

This manor arose from Turbern’s five hides held under the Earl of Warwick. By the early 1200s Simon Bagot and Henry le Notte held it jointly as one knight’s fee. When Simon Bagot died (1242–3) his portion had already been disposed to sub-tenants, and the record states that the land “had passed to the Knights Hospitallers, who held intermediately between the Earl of Warwick and the heirs of Simon Bagot.” (Bk. of Fees II 957).

Henceforth the Bagot moiety was Hospitaller, while the le Notte moiety remained Templar, forming together a single fiscal unit until the Orders’ suppression.

V. Temple Balsall and the Templar Order in Warwickshire

Founded in the mid-12th century, the Commandery of Balsall served as the central house of the Knights Templar in Warwickshire. It governed estates across Balsall, Claverdon, Rowington, Kineton, and beyond, with a preceptory, chapel, and grange system linking the region’s manorial lords. Records in the Rotuli Hundredorum show the Templars holding of the Earl of Warwick the lands “in Kington and Preston adjacent,” directly overlapping the le Notte estates.

Thus the le Notte family were not mere tenants, but co-administrators and noble knights-fee holders within the Templar jurisdiction, their lands forming part of the Balsall commandery’s military-monastic system. Each knight’s fee represented the support of a fully armed knight for the king’s service, signifying formal noble rank in feudal law.

The Hospitaller Succession

When Simon Bagot’s heirs came under the Hospitallers mid-13th century, Warwickshire thus contained both Orders in juxtaposition — Templar on the le Notte side, Hospitaller on the Bagot. After the Papal Bull Ad Providam (1312) and its royal execution (1313–1314), Temple Balsall and its dependent manors — including the le Notte half of Kineton — were transferred to the Knights Hospitaller. This ended the dual administration formally, though locally the families continued in hereditary possession as lay lords.

The Cultural Order

The Templar presence brought not only fortification but civic development: market charters, sheep drives, cider presses, and fair rights administered through their preceptories. For noble families like the le Nottes, integration with the Order meant elevated status — participation in a trans-European network linking Warwickshire to the Holy Land.

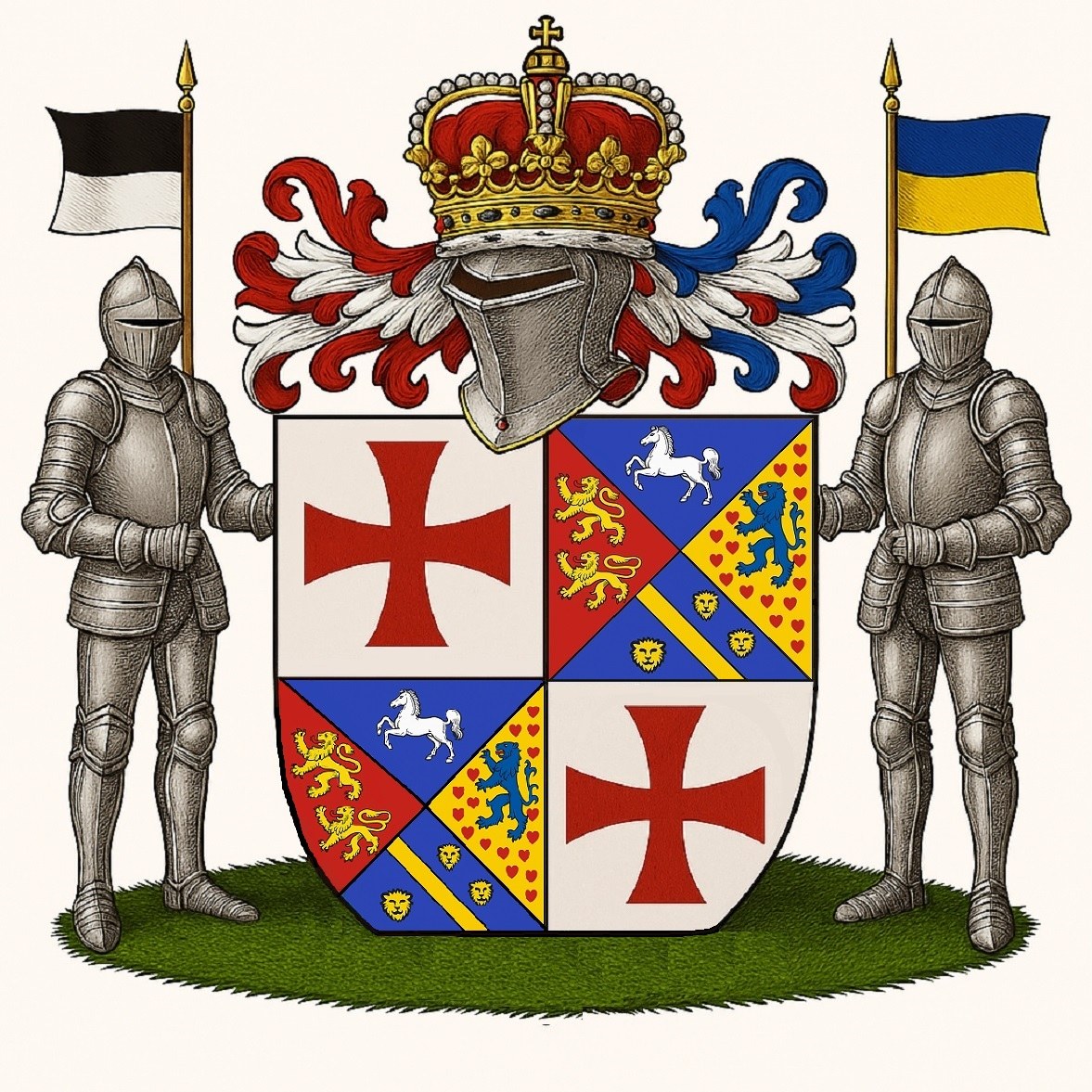

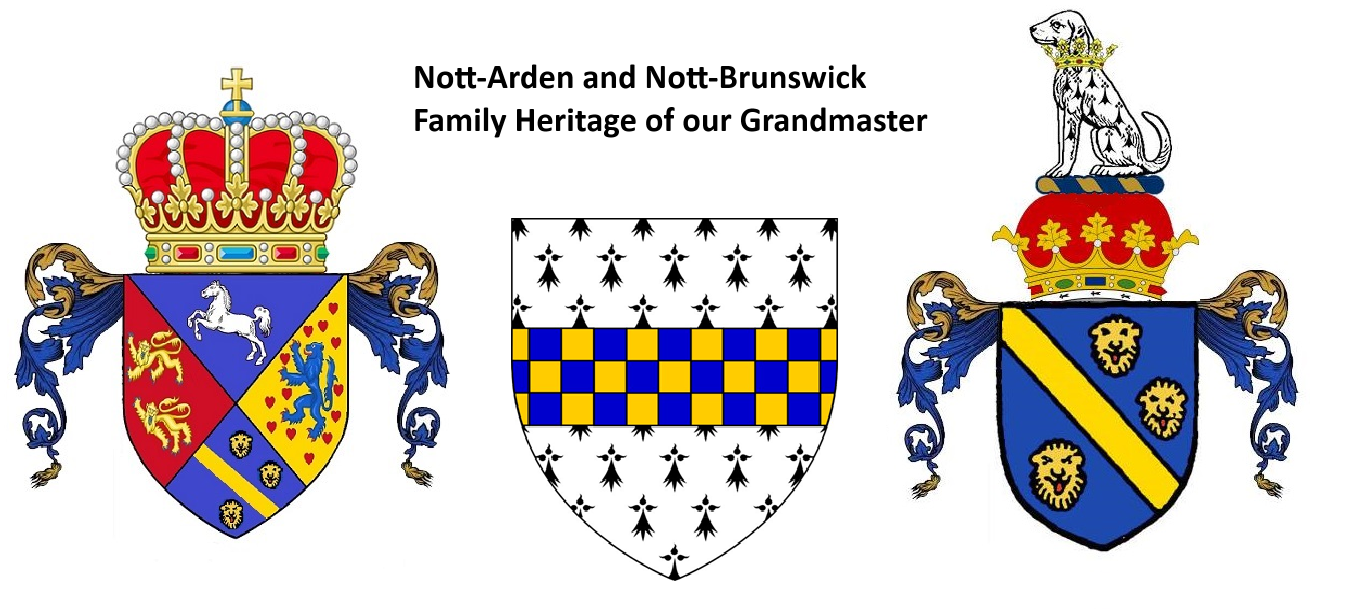

VI. Heraldry and Lineage of the le Notte Lords

The arms borne by John Nott, Lord Mayor of London (1363–64) — Azure a bend or between three lions’ faces or; crest, a talbot sejant ducally gorged ermine or — were authenticated by the College of Arms in 1575 as those of the descendant house of Nott-Arden. These same arms are carved and painted in the church and manor buildings of Shelsley Beauchamp, confirming the continuity of the line.

The heraldic devices carry ancient significance:

-

le bend or on azure — one of the oldest and most exclusive English charges — denoted royal service under the kings of Mercia and later under Arthurian legendary tradition.

-

The three lions’ faces recall the arms of England itself, symbolizing watchful loyalty and kinship to the royal line.

-

The talbot crest, collared with ermine ducal fleurs, signals a formerly reigning royal house by right of blood.

From John Nott VI of Thornbury-Kington (m. Anne Jeffreys, daughter of the High Sheriff of Worcester) descended the Shelsley lords who migrated to America in the seventeenth century — John Nott of Wethersfield, Connecticut, recorded in Connecticut state encyclopedias as “grandson of Lord John Nott of Nottingham.” These trans-Atlantic records preserve the family’s noble identity long after the formal titles were absorbed.

VII. The Arden Continuity and Anglo-Celtic Heritage

The Arden house represents the last native English baronial line to survive the Norman conquest. While other Saxon families were dispossessed, the Ardens — and their cadet branches such as the le Notte family — retained lands “of baronial dimensions.” Their blood is traceable to the Mercian and West-Saxon royal line through Cuthwine, Ingild, and Aethelwulf. By inter-marriage with Celtic (Welsh) princesses as mandated by King Ine’s law, the Ardens formed the Celtic-Saxon noble synthesis that defined England’s Christian aristocracy.

That heritage was carried forward in their service to the Templar Order — a religious-military institution that itself embodied the union of faith and knighthood.

VIII. Significance of the Kineton Pattern

The repetition of four Kinetons (or Kingtons) under one vicecomital house cannot be dismissed as coincidence. Their distribution aligns with:

-

the bounds of the ancient Kineton Hundred,

-

the estates enumerated under the Templar and Hospitaller rolls, et

-

the linguistic markers of cyngtūn — the king’s estate — throughout Arden.

This pattern affirms the existence of a coherent noble jurisdiction stretching from Packington in the west to Kineton-on-Edgehill in the east, forming a microcosm of Mercian and early English governance.

Through the le Notte and Bagot co-administration, we glimpse a model of continuity — a bridge between Saxon, Norman, and ecclesiastical sovereignties — preserved in the layered record of feudal England.

IX. Conclusion — The Mandate of Memory

The evidence drawn from Book of Fees I 508; II 957; Rotuli Hundredorum II 226; and Dugdale’s Antiquities compels renewed attention to the Four Kinetons of the Ardens. Here was no scattered coincidence of manorial names, but a surviving earldom of eternal inheritance, managed by vicecomital lords of Templar association who embodied both the Saxon and Norman ideals of chivalric governance.

The suppression of the Templars dispersed their institutional framework, yet the memory of their Warwickshire commandery — intertwined with the le Notte family — endures in the landscape and parish stones of Kineton, Packington, Solihull, and Preston Bagot.

Today, as heraldic emblems are rediscovered in Shelsley Beauchamp and the genealogical line traced across continents, the mandate of this history is clear: to restore awareness of England’s oldest surviving noble house — the Ardens and their cadet branch, the le Nottes of Kineton — whose stewardship of the land, faith, and crown was neither extinguished by conquest nor forgotten by time.

References (inline):

-

Book of Fees, Vol. I, p. 508; Vol. II, p. 957.

-

Rotuli Hundredorum, Vol. II, p. 226.

-

Dugdale, The Antiquities of Warwickshire Illustrated (1656).

-

Keats-Rohan, Domesday Descendants (2002), pp. 288–308.

-

Inquisitiones post dissolutionem Templi, 1313–1314.

-

Charters of King Edgar (S 773), British Library & Sawyer Archive.

Appendix A — Evelyn Philip Shirley on the Ardens of Longcroft

“No family in England can claim a more noble origin than the house of Arden, descended in the male line from the Saxon Earls of Warwick before the Conquest.

The name of Arden was assumed from the Woodlands of Arden, in the North of Warwickshire, by Siward de Arden, in the reign of Henry I.; which Siward was grandson of Alwin the Sheriff in the reign of Edward the Confessor. The elder line of the family was long seated at Park-Hall in Warwickshire, and became extinct in 1643. A younger branch descended from Simon, second son of Thomas Arden of Park-Hall, Esq., settled at Longcroft in the parish of Yoxall in the reign of Elizabeth, and now represents this most ancient and noble family.See Dugdale’s Warwickshire, 2nd ed., vol. ii, p. 295; Shaw’s Staffordshire, vol. i, p. 102; and Erdeswick, p. 279; also George Ormerod’s paper “On the Connection of Arden or Arderne of Cheshire with the Ardens of Warwickshire,” in The Topographer and Genealogist, vol. i (1846).

Arms — Ermine, a fess checky Or and Azure, borne by Sir —— de Arderne in the reign of Edward II.

Present Representative, George Pincard Arden, Esq.

(Quotation from E. P. Shirley, The Noble and Gentle Men of England, p. 233 — Oxford & London: John Henry Parker, 1859.)

Appendix B — Maps of Kineton Cyngtun

Map 1 (Original grant)

Map 2 (The Kineton Hundred, borders overlapping several Shires, with all 4 Kinetons within the Arden realm)

Map 3 (Western Arden)